Blackness and the Future Part 2

Black folk’s hyper awareness of being perceived stems from deep historical wounds inflicted by slavery. The idea of being found at the wrong pace at the wrong time is a narrative that has perpetuated throughout Jim Crow and is prevalent today for Black Americans through hyper policing and the result of mass incarceration. The history of policing in America is a great example of this idea of being black at the wrong place and time. One of the laws instituted during Jim Crow was the creation of Sundown Towns also known as Sunset Towns. Sundown towns are small suburban towns in America that black people were not allowed to be in after dark. If found in these towns after dark Black people would be arrested, beaten, and subjected to any and all violence. Many black people worked in these towns during the day and had to return back to the adjacent cities where they resided. This law allowed white people to commit crimes against black people without consequence because it made it the Black person’s fault to be in the small town after dark putting them at the wrong place at the wrong time.

This was another way for police to have access to Black people without black folk actually committing any crimes. This gave excuses for mass arrest and public violence through lynchings of black individuals for petty crimes or nonexistant crimes. In James A. Manos’s From Commodity Fetishism to Prison Fetishism he addresses the impact of slavery on the modes of punishment “nonetheless, without incorporating the narrative of convict-leasing, we fail to see two things: how the modes of punishment shape the modes of production and how they concentrate and reproduce the ever-increasing dispossession of capitalism as a form of racist dominations.” The prison industry is intrinsically racist. We simply cannot begin to talk about the current prison industrial complex without addressing convict leasing, jim crow laws, and slavery. Current mass incarceration of black folk is directly related to the racist American history at large. Coined by Dr. Angela Davis, the term Prison Industrial Complex helps us understand the involvement of government, and the larger social, political, and economic context of the prison industry.

Mass incarceration is a legacy of slavery therefore it is directly linked to slavery and its aftermath. We cannot see current day policing and incarceration separate from the violent racist history of America. Achille Mbembe in Six The Clinic on the Subject summarizes,

“To be Black is to be stuck at the foot of a wall with no doors, thinking nonetheless that everything will open up at the end. The Black person knocks, begs, and knocks again, waiting for someone to open a door that does not exist. Many end up getting used to the sensation. They start to recognize themselves in the destiny attributed to them by the name. A name that is meant to be carried, they take something they did not originally create and make it their own.”

So then my question is now that we are here in a racialized society under a skin and an identity we cannot escape, an experience assigned to us at birth and assigned to our ancestors where then can we go, what then shall we do? Marcus Garvey, similar to other pan african theorists identifies the idea that “for this distinct possibility to be realized” meaning the full liberation of Black people world wide, “ the Blacks of the Americas and the Caribbean had to desert the inhospitable places to which they had been relegated and return to their natural habitat and occupy it once more.”

While I agree that could be one way to restore the full liberation of Black people world wide, I question the possibilities of that happening in this globalized world. The mere system and infrastructure of america is built on genocide and slavery therefore the system was not built on the survival of the oppressed in mind. How can this monstrous system be reversed? Is Africans returning to the homeland the only solution to true liberation? What other ways can we be fully liberated on American soil?

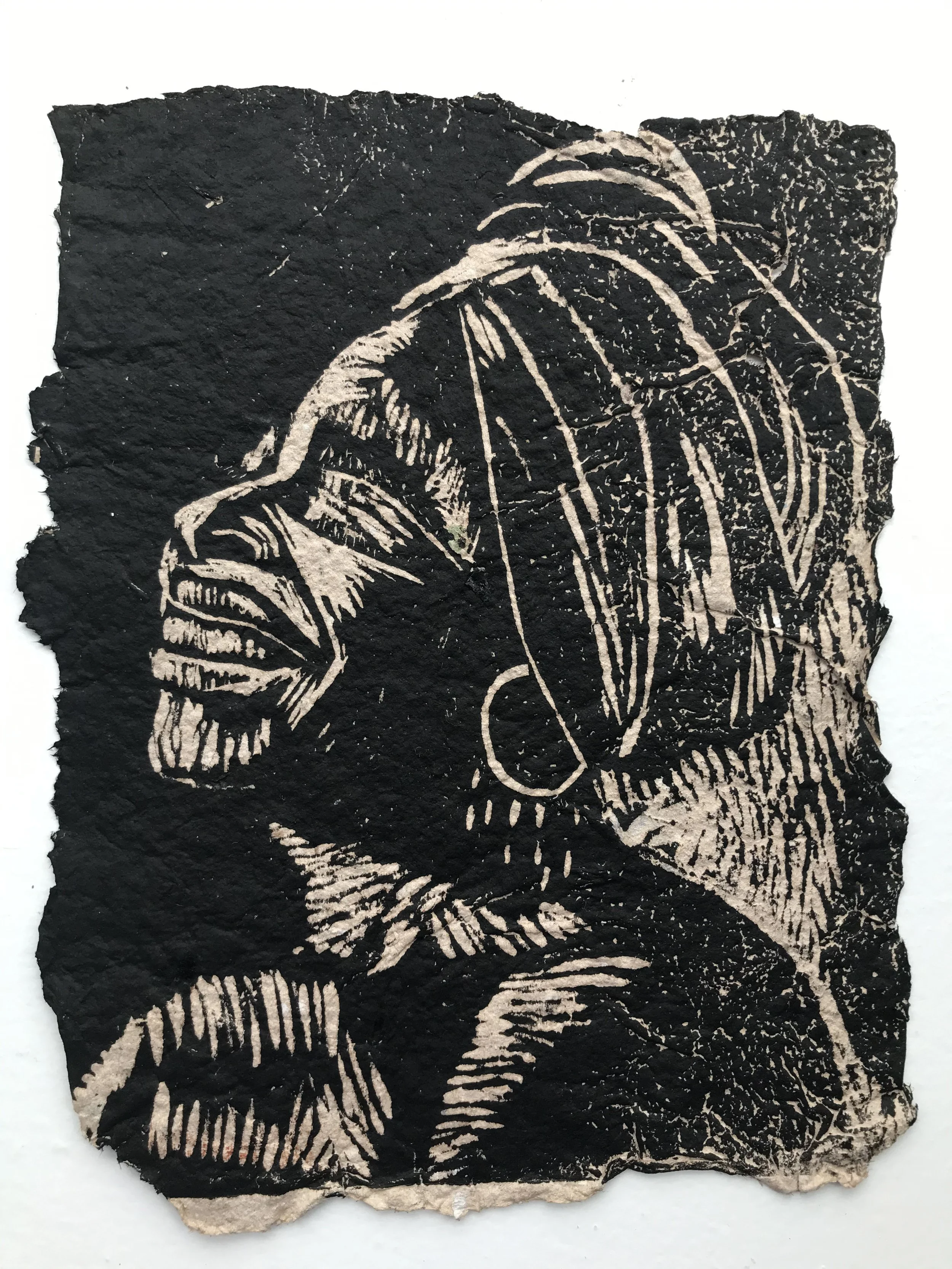

What now? What is the future like for black folks in America? Many artists, writers, and thinkers have imagined black futures both in reality and fiction. In reality by paving a better path for the following generation in shifting policies and advocating for a better future. Through fiction famously known as Afrofuturism declaring a liberated future for Black folk. Through this genre black authors, thinkers, and artists create a future only they could imagine that puts black folk at the center of a world that is created with them in mind rather than the alternative. People who have created afrofuturist books and movies include Octavia Butler, Nnedi Okorafor, Colson Whitehead, and artists including Wangechi Mutu, Sun Ra, Genel Monet, and one of my personal favorites Alisha Wormsley. These individuals and many more are influential in the creation and development of this genre. Alisha Wormsley There are Black People in the Future was about claiming space by declaring this statement repeatedly on billboards, and carrying signs. I think about this piece both in conversation and juxtaposition with Fanon's writing on the consciousness of the black person, and on the idea of recognition. In Black Skin White Mask he navigates the symptom of colonialism which is black people in the Antilles wanting nothing to do with their blackness. Wanting to be more like their oppressors. Because they as black people have been painted inferior and their only way to be worthy is to be more like their oppressors. “The question is always whether he is less intelligent than I, blacker than I, less respectable than I. Every position of one’s own, every effort at security, is based on relations of dependence.” Meaning that the value of a black person is made to be always in relation to either another black person or a white person. Similarly Malcolm X spoke in 1962 and addressed “who taught you to hate the texture of your hair? Who taught you to hate the color of your skin?...” This is a symptom of slavery and colonialism because the oppressed and the colonized are always made inferior by their oppressor.

What it means to be Black in the world more specifically on American soil is complicated. But largely it means to wear the skin assigned to you and navigate the world according to the history of your people and your ancestors before you. As many thinkers and theorists investigated in the past, the consciousness of a black person is wrapped up in the consciousness of the constructed racial and colonial world. And the liberation of a black person in these systems is deeply tied to the release of the colonial and systemic bondages. How do we do that? I dont have the full answer to that question. I know the system needs to be brought to question and dismantled. The system that is the people we put in power, the education we teach our young, the prisons system, health care… and many more.

Written: December 5, 2023

Comfortable in Silence

Institutions are comfortable in silence ———

Despite how loudly they hear the cries,

Of the atrocities fed by their dollars,

Cries of souls under the rubble,

Of bare-handed children mining minerals,

Of parents cradling their dead,

Of elders who have witnessed this terror a thousand times,

Cries, mourning, suffering, death, and destruction,

Yet dare not lose hope in humanity,

Academia is comfortable in theory

————

Comfortable in reading about human atrocity after it’s played out,

In classrooms where the distance provided by time,

Shields them from their would-be complicity,

Refusing to act when history is writing itself right outside,

Uncomfortable when students miss class to join the sorts of movements praised

In cushy classrooms,

Clearly genocide conflicts with the syllabus,

Leaving less time to debate the politics of people’s humanity,

Students are told they don’t need to be loud about what’s happening,

But if you’re not loud now, then when will you be?

Don't you see the dissonance?

The cup of coffee you clasp in your hands,

Is filled with blood,

Yet you gulp it down all the same,

As you lecture on the injustices that permeate our collective history,

Where did your wires become crossed?

It's not that you don't see the evidence of

Colonialism and imperialism,

Death and destruction,

Caused by greed that feeds capitalism,

Because by your own admission,

You have dedicated your life to its “study,”

You see the devastation of land and human beings,

The silencing of your colleagues, You are very well aware,

You just couldn’t be bothered to care,

If the people suffering are black, arab, or muslim,

You claim it to be your expertise,

There’s nothing you don’t know,

And you are eager to impart all you’ve learned,

Connecting it back to the philosophies of dead old men,

Who stood to benefit from the ageless violence,

But when called to help liberate those people from their suffering,

You have no interest,

You don’t want to invest in the living,

You much prefer to read about it,

Once the dust has settled,

And all that’s left is theory.

Written~ December 10, 2023

Published~ February 12, 2024

Bear Witness

What does the future hold after we look at the history of America through the Black experience? The future is directly influenced by the present so I would like to ground the question in the now. And ask what are our responsibilities to the present so that we can imagine the future? We play an active role in shaping the history of the future whether or not we believe the magnitude of the role we play.

Our global struggles are often deeply interconnected as humans, especially as globally oppressed peoples. Whether that is racism, class, ableism, colonialism, or imperialism. They are interconnected because we are governed under a system that doesn't imagine a future with us in mind. Rather it imagines a future where capitalism and exploitation are centered and not the well-being of all people. And the instigators of these issues are colonial and imperial powers that have built these systems on the backs of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Our recognition of these systems and their global power is critical in our imagination of the future.

For our imagination of the future, we must be present and bear witness to the injustices happening around us. We can't move to change anything if we cannot acknowledge what needs to be changed. I often think back to what I was taught about history in high school. I wonder now who controlled the narrative. Did the subjects of our textbooks have a say in the writing of their story? Whose stories were left out? When the main historical narrative we are fed is written by the oppressors, their greatest crimes are conveniently omitted. History is often not a factual documentation of what happened so much as a retelling of what the oppressor wants us to remember. Such material does not bear witness to the realities of the past, nor does it teach us how to bear witness to the realities of our present. I don’t want to see a future or leave a future for the next generation that is imagined by the oppressors who refused to bear witness.

To bear witness is to be present and to reckon with what we’re witnessing. It is critical to creating a more just world. Being present can take many forms... For me it means learning as much as I can about what is going on in the world, participating in efforts to destabilize inhumane acts of empires through boycotting, protesting, calling, signing etc. But it's also not limited to these actions. Bearing witness for me is also the mere act of reckoning with the present and allowing myself to digest what's happening around me. Fleeing from these issues as if they don’t pertain to us is the main problem and it is a huge privilege to be able to distance ourselves. Bearing witness to the present is also allowing ourselves to grieve and not accept the realities as normal.

I remember when I first arrived in the US at 13 years old. Growing up in a country of Black people, I had no knowledge of the construct of race or how that construct would be ascribed to me. I had a vague understanding of slavery in America, but not its lasting impact or complexity. It didn't take me long to realize my skin had a lot to do with how I was perceived.

I was a freshman in high school when Eric Garner, a 43-year-old black man, was murdered by the police. That same year Michael Brown was also murdered by the police. I remember watching Eric Garner’s murder on the news. I remember how traumatic that was to witness even on television. Now that I have the words for it, I realize what the publicizing of violence committed against Black people does to the psyche of everyone involved. That was the first time I bore witness to the violence and injustice that plagues Black Americans, but it sadly was not the last.

I was still learning English at the time, but I remember arguing with my peers about how wrong the killing of this Black man was. They kept telling me he was a criminal. I was so baffled at the thought of someone publicly executed without a trial, criminal or not. As Eric Garner stated many times, he couldn't breathe with the knee of the officer on his head. They had every chance to let up, to let him breathe, and they didn’t. I argued with the little English I spoke for the humanity of this man who looked like me. I had this argument with children and adults alike. Years later during the summer of 2020, I once again had to argue for the humanity of a Black man murdered with the knee of a police officer on his neck, a Black woman murdered asleep in her own bedroom, and another Black man murdered while jogging. There was a global outrage following the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. Calling to question the constant brutalization of Black bodies in America. However, this outrage was not present on the campus of my small, midwestern university. There was no talk, action, or conversation from my non-Black peers and professors. My fellow Black students and I had undertaken the burden of making sure everyone bore witness, even in the face of them constantly denying our humanity. I was shocked by the dissonance I encountered while studying at this predominantly white university. I was expecting people to wrestle with the current crisis unfolding in front of them. Yet they chose to be silent and decided it didn’t concern them.

It's that disconnect I am bringing into question when I think about our responsibilities as humans to bear witness. Especially now as we are witnesses of atrocities in Palestine, DRC, Tigray, Haiti and many more countries across the globe all suffering from some sort of global power and extraction. I am questioning the delusion that people think they can exist outside of politics. They say, “This is too political for me.” They are not troubled by what they see because they make no time to sit with it and digest it. They believe what the western media tells them to believe. The acknowledgment of the interconnectedness between most geopolitical and social issues is critical for us to bear witness to these atrocities. It affects us no matter how distant it feels because we are governed by powerful empires that have extracted and exploited people everywhere. The issues we often deal with globally usually have common instigators.

Blackness and the Future Part 1

What does it mean to be Black in America? This question has been posed by many scholars and thinkers for decades. From Frantz Fanon to Toni Morrison, Angela Davis, Marcus Garvey, and many more. All Black scholars reckon with this question that is intrinsically connected to their lived experiences as Black people in a country born from colonialism and race-based slavery – a world that was not constructed for them. They are forced to interrogate the current socio-political system, questioning its origin, and the role it plays in the Black psyche. Being black is a position that is assigned by an external force; it is then a position acknowledged and understood as one’s own identity. Once “Black” is ascribed to a person, the way they move about the world and the role they fill is dictated by the color of their skin. In The Clinic of the Subject, Achille Mbembe states that “those clothed in the name Black are well aware of its external provenance” that is to say being Black is deeply intertwined with an experience of hyper-awareness. Mbembe continues, “They are also well aware that they have no choice but to experience the name’s power of falsification.” Existing in the world as a Black person is the expectation of being misunderstood because under the current system, there is no room for them to be seen outside of their Blackness. Being Black as W.E.B. Du Bois stated in The Souls of Black Folk is also “[a] double consciousness…measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” To be Black is to be burdened with an awareness of how you are perceived that fights to eclipse your sense of self.

The everyday lives of Black people in America are painted by this double consciousness whether today or decades ago – an unwelcome constant. Some experiences heighten this feeling of “double consciousness”, such as the hyper-awareness of one's own body when out in predominantly-white public. When you are Black, encounters with the police, going to the park or supermarket, walking at night, wearing a hoodie, or merely just existing in predominantly-white spaces can lead to bodily or emotional harm. This awareness has allowed Black people to develop methods of navigating white space more safely. Fanon investigates this double consciousness in Black Skin White Mask by stating “The black man has two dimensions. One with his fellows, the other with the white man. A negro behaves differently with a white man and with another negro.” Though this concept was initially investigated by Fanon, in recent years this idea has largely been referred to as “code switching.” This term was coined by a sociolinguist Einar Haygen in 1954. Code switching is widely used with black people and other people of color in the United States to maneuver space occupied by the white majority by mirroring their speech patterns and behaviors.

Being Black in America is to live within a series of concentric falsehoods. You are perceived incorrectly, as an inferior and a threat, and so to combat that you must behave inauthentically, adopting the colloquialisms and behaviors of those who do not see you as you are. All the while, you are trying to hold onto any true sense of who you are. This hyper awareness of your body caused by constant surveillance leads to the idea that Black people need to be performing in the public eye. Where does this surveillance of Black people start in America history?

A Strong Black Woman

A Strong Black Woman

What it means to be a Black woman in America is a question with layers too complex to unravel. While there is no one answer, in this article I attempt to navigate what safe spaces look like in the everyday experiences of Black women at predominantly white institutions. Studying Black women and their everyday experiences exposes significant truths about the fabric of our system and the many ways America has failed and subjugated Black women. Black women are constantly resisting preexisting negative stereotypes in spaces they inhabit. This psychological battle against systemic and historic rhetoric hinders Black women’s mental and emotional wellbeing. Being a Black woman in a White institution adds new layers to the complex issues of the racialized trauma Black women carry every day. From microaggressions to physical and emotional safety Black women are constantly resisting.

Since slavery Black women have endured social economic disenfranchisement, everyday negative stereotypes, and political and systemic oppression. Black women have been battling for emancipation since the era of slavery. They are still in pursuit of liberation centuries later and are living the implication of systemic racism. Angela Davis in Women Race and Class explores the experiences of enslaved Black women in order to understand Black women’s current battle for liberation. Studying the lives of enslaved Black women gives us significant insight into the system and structure of the lives of Black women and the make-up of the Black family as a whole on American soil. Reading Angela Davis made me question our behavior in space as Black women and the struggles we endure every day. What are the roots of negative stereotypes against Black women? What are the unsaid expectations for Black women? What are some conscious and unconscious behaviors people uphold towards Black women?

The Strong Black Woman Myth

“You are such a strong Black woman.” This seemingly complimentary phrase has deeper implications than what people often assume. Black women are constantly praised for their strength. Being strong for Black women was not a choice. In my conversation with Talandra Neff professor of teacher education she explains, “there is no other option than the Strong Black Women. We had to be”. This strength mentality is a psychological state that Black women had to enter into not because they wanted to, rather because they had no other options. This myth communicates that Black women are supposed to be strong, shed no tears, and show no weakness of any kind even if they are falling apart internally. Why is that? And why is it that this is a “compliment” that Black women receive? What are the ways in which this persona is hindering Black women’s well-being?

Many Black women suffer from severe depression, yet still maintain a composure of strength. In Too Heavy a Yoke: Black Woman and the Burden of Strength, Chanequa Walker-Barnes states that, “The StrongBlackWoman [SBW] is a legendary figure, typified by extraordinary capacities for caregiving and for suffering without complaint” (3). As I interviewed Black women at Indiana Wesleyan University– both faculty and students— it wasn’t a revelation that our conversations naturally led to our experiences of the everyday burden of strength as Black women. Although questions about the narrative of SBW was on my list of questions when I interviewed these individuals, even before I mentioned the phrase ‘strong black women’ they alluded to it when asked about self-care. Black women are hyper aware of the perceptions and pressure of society to constantly be strong and keep a certain composure. One of the questions I asked each participant was how they practiced self-care. We often put our needs aside to help others. Many said that they often don’t have the time to care for themselves because of their obligations and what is expected of them. Saying no to requests is something that is difficult to Black women especially at predominately white institutions. The scarcity of black individuals at predominately white institutions puts pressure on Black people to show up in every space and speak about race related topics even if they didn’t receive a formal race relation education. And there is always the pressure of if I don’t then who will?

Black women quite literally raised and nursed America. Although the Strong Black Woman myth is birthed out of the narrative of the black mama figure that is nurturing and caregiving, Angela Davis reminds us that the experiences of enslaved Black women wasn’t limited to raising children. They not only cared for babies, but they also picked cotton and experienced flogging just like Black men. Davis writes, “The slave system defined Black people as cattle. Since women, no less than men, were viewed as profitable labor-units, they might as well have been genderless as far as the slave owners were concerned” (5). Black women were and are resilient. They endured for the future of Black women. They endured not only because they were Black, but also women. Chanequa writes:

“although Black men’s and Black Women’s identity have been bound by cultural mandates to be strong, the manifestation of strength that has become normative for Black women is uniquely racialized and gendered. Strong is a racial gender codeword. It is a verbal and mental shorthand for the three features of the strong black woman—caregiving, independence, and emotional strength/regulation” (3).

When you are constantly praised for doing well and being strong, “you almost feel a little bit of shame when you are not doing it as well as you think you should” (Talandra). Which, in turn, adds more pressure on you to perform well to keep at that level of excellence even if you feel like you are crumbling inside. This expected excellence is toxic and exhausting. Often it seems that to be accepted by society as a Black woman we have to be the exception. This is especially relevant at Predominantly white institutions. Since it is not believed by society for us to “make it” there is an unconscious pressure for us to “prove” that we can. As Black individuals as Predominantly white institutions, we often find ourselves needing to prove our credentials. “yes I made that art work”, “yes I wrote that article”…Many stories were shared at our protest as Black Student Union that made this point even clearer. Black student’s dorm rooms were searched for no reason, some were stopped by campus police and asked if they possessed drugs in their car. All of these incidents send a clear message that we “don’t belong” . The need to consistently prove our excellence and our belonging, perpetuates a cycle of exhaustion.

Black people at predominately white institutions are often seen as experts on issues of race. Most of the Black women I talk to are honored to speak, train, or be involved in different circles. These opportunities allow them to bring their whole self and culture into new spaces. The problem lies when non-black people don’t honor and see Black people, especially Black women, as whole people. They are only sought after because of what they bring to the table. Neff expressed frustration at this reality saying, “I just wish for 3 hours with someone who doesn’t need me or isn’t asking me for something.” It is not just faculty that is often volunteered or requested to be in these conversations, but students in many areas have been looked upon as if they are the oracles. In our conversation, Dr. Farmer, professor of Practical Theology, stated that “because the ideal is to produce, it is easy for black and brown bodies to feel extracted from.” Therefore, they are not compensated for their wisdom and time. As Black people we naturally center our stories by advocating and holding space for each other. However, it shouldn’t only be expected from us to do the work of fighting racism. Racism is a disease that infiltrates the fabric of our system. It feels as though white people are quietly sitting and watching rather than doing the work of antiracism themselves. Often in white institutions racism is a topic, if at all discussed, treated as this far away concept perhaps something that exists almost theoretically. But confronting racism is not acknowledging that racism exists and that it is real, rather it is being anti racist and doing the work to fight unjust systems and personal biases. However, white institutions are waiting on black and brown bodies to do the work. This makes us feel like we are a commodity, not as wholistic humans who have other interests and passions. Believe it or not we don’t enjoy rehashing our trauma so that white people can learn something. Often, we sacrifice our own mental and emotional well-being so that just maybe something would sink in.

In my conversation with Jhinika Luve a recent graduate of IWU, we discussed the importance of honoring our stories. Often in predominantly white institutions, People of Color (POC) are asked to share their stories and their experiences with racism. This discards our mental and emotional well-being. In our conversation, Jhinika stated, “One way I am learning to take care of myself is that I don’t have to hold the responsibility of sharing my experiences with people.” Black people, whether in casual conversations or formal settings are asked to share their stories to enlighten white people or get their ‘perspective’ on the issue. Jhinika expanded by saying “When I relive a traumatic experience to educate somebody… I may have to cancel my whole day because having that now in the for the front of my mine has made me shut down emotionally so much where it is crippling.” The same way we don’t blatantly ask people about the most traumatic part of their stories we should as well be cautious of how easily we discard Black people’s trauma. As Black individuals, we already see how the world doesn’t value our lives through news and political warfare. The normalization of Black death has become a causal coffee table conversation. But for Black people, it is not just something we discuss for the sake of conversation. We associate with the lives lost, with the headlines, and with the hashtags. The people dying at the hands of white police officers look like us. While America is sending a clear message of how little regard it has for our lives, we don’t want to be in conversations with white people who want to disuse the recent headline with us just at the drop of a hat. Like we are buckled up and ready to listen to what their uncle or dad thinks about it. The issue of racism is not up for debate it shouldn’t even be an opinion. It is a fact. Often in white circles the topic of race and race related trauma is discussed in a lighthearted manner as if it is a matter of preference or point of view.

All scenarios listed above are ways in which Black women don’t feel safe in predominantly white spaces. They suffer the pressure of expected strength and excellence, extracted stories, and exhaustion from overextending. As Black women we find safe spaces at predominantly white institutions by creating safe spaces for ourselves. We create these safe circles among other Black individuals. Creating spaces for ourselves and prioritizing ourselves is not easy, but it is something we are constantly learning to grow into. If you are Black you already know these scenarios, maybe one of the stories listed hits close to home. My message for you is to honor your story. You belong and the space you hold is essential and critical. If you are non-black and you are reading this, think about the space you hold in society. Are you doing the hard labor of moving towards anti-racism? Are you holding an intentional space for your fellow Black friends?